Special thanks to Katie Chicquette Adams, a public school teacher, for this guest blog post.

I’ve worked downtown at Appleton’s alternative high school program as its Language Arts teacher

for ten years. Students at risk of not graduating, of losing housing, health, or safety, of feeling lost

and misunderstood are my daily companions. I have a learned a great deal from them. They might

seem like unlikely candidates for willingly studying a 200-hundred-year-old novel, but when it comes

to Frankenstein, they are predictably game.

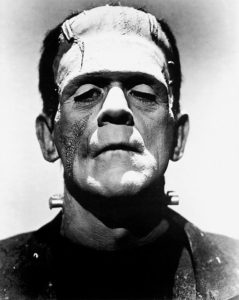

One of my favorite moments is when Victor first confronts his creation, angrily hurling epithets and threats—and to at least some extent, quite understandably. He believes (correctly) that his “offspring” has murdered his younger brother, a mere child. The miserable creature says, “All men hate the wretched,” and its truth resonates painfully. Yes, we want to hate Victor (and everyone in his society) for rejecting the friendless fiend so unequivocally. My students started discussing the idea that we 21st century types like to think we are way less judgmental and dismissive than people of the past, but it’s a false narrative. Nobody really disputed this.

One of my favorite moments is when Victor first confronts his creation, angrily hurling epithets and threats—and to at least some extent, quite understandably. He believes (correctly) that his “offspring” has murdered his younger brother, a mere child. The miserable creature says, “All men hate the wretched,” and its truth resonates painfully. Yes, we want to hate Victor (and everyone in his society) for rejecting the friendless fiend so unequivocally. My students started discussing the idea that we 21st century types like to think we are way less judgmental and dismissive than people of the past, but it’s a false narrative. Nobody really disputed this.

It made me next think of several moments I had just read in Evicted by Matthew Desmond.

One: He points out based on his research of extremely low-income renters in Milwaukee that, “Trailer park residents rarely raised a fuss about a neighbor’s eviction, whether the person was a known drug addict or not. [They implied that] [e]victions were deserved, understood to be the outcome of individual failure. ‘They helped to get rid of the riffraff,’ some said. No one thought the poor more undeserving than the poor themselves” (179-80).

Another: the about-to-be-evicted Larraine calls every single aid agency she can (she is ineligible for them all), asks her daughter for money, and finally her church where the pastor routinely preaches about the importance of caring for the poor. He has given her a loan from church before, which he believes did not go to good use. He struggles to decide if this is wise to keep doing, as he “believed a lot of [her] hardship was self-inflicted,” and by many accounts, this can be seen as, at the very least, partly correct. In the end, Larraine’s own sister advises the pastor against another loan, despite the pastor’s regular incitement to parishioners to help those in need in our world. Desmond states: “It was easy to go on about helping ‘the poor.’ Helping a poor person with a name, a face, a history, and many needs–that was a more trying matter” (127).

Victor’s creature is tormented from “birth”–like so many in the class of renters Desmond writes

about. He eventually makes unwise choices that are barely forgivable out of his own trauma—but

only after trying for a long time to do the right thing, to walk the upright path. He begs for simple, yet

terribly complex solutions to his problems. Surely, people in Shelley’s time prided themselves, as

many do now, on the ability to soft-heartedly love all of creation, even its most wretched–but when

confronted directly with a wretched individual (the creature), they have only one reaction: scorn,

hate, rejection. Every. single. time. Even after he saves a peasant’s daughter from drowning!

At their first meeting, the wretch later assures Victor: “I was benevolent and good; misery made me a

fiend.” In his last monologue, long after the sum of his crimes have been committed, he asks, “Am I

to be thought the only criminal, when all human kind sinned against me?” He knows his question has

no good answer; he knows there can be no real mercy.

The individuals providing Desmond’s research know this as well. Their reactions to nearly unlivable

situations range from merely unwise to technically illegal—as do some of their landlords’ actions.

And in that moment, the creature’s comment rings true: we feel little love for this. We want to say,

“well, but…that is wrong,” even as still greater wrongs perpetrated over months, years, and even

generations influence every aspect of their existence. And those fortunate enough to be afforded the

opportunity to be wise—they are stuck, unable or unwilling to offer what they can: resources,

counsel, grace.

Humans are strange. We know there are hurting people. We know hurting people make bewildering

and at times destructive choices. We are, generation after generation, stunted from ever figuring

out collectively how to deal with this.

You can learn more about Evicted and Matthew Desmond’s upcoming talks here.

Katie Chicquette Adams is an educator and writer in Appleton, WI. Her work has appeared in River + Bay, Mothers Always Write, Heavy Feather Review, The New Verse News, Riggwelter, Poets Reading the News, and on the regional blog, Storycatchers. She is a live storyteller with Storycatchers, Inc. and works as an English teacher for at-risk young adults at a public alternative high school, with hopes they will remake their own stories, and become friendly with at least one poem. She can be reached at k.chicquette.adams@gmail.com.